Nuevas palabras

Wall-E: The robot who reminded us how to be human.

There are movies that entertain, others that move, and a few that, without saying a word, teach you the essentials. Wall-E is one of those. A small, rusty, lonely, curious robot… with more humanity than many humans. On an empty planet, covered in trash, where civilization decided to leave because it was easier to escape than to repair, Wall-E continues doing his job. Day after day, silently, he picks up, arranges, cleans. And all the while, he collects things. Things others threw away. Things no one valued. Like someone who unknowingly keeps pieces of hope.

When children watch Wall-E, they’re not just seeing an adorable robot who falls in love with a modern space probe. They’re seeing the power of perseverance, of tenderness, of curiosity. They see what happens when someone, instead of giving up, decides to care. And to care without anyone seeing it, without anyone rewarding them, without applause or followers. Just because. Because it’s the right thing to do.

From a child psychology perspective, Wall-E touches deep emotional development. Wall-E lives in a desolate and silent environment, yet maintains a profound inner world. This reflects, in many children, the capacity to form emotional bonds even in cold or disconnected environments. Wall-E represents emotional resilience, the ability to sustain hope and connection even in isolation.

Furthermore, this little robot is fascinated by insignificant objects: a fork, a lightbulb, a Rubik’s cube. This is no coincidence. In childhood, symbolic play is one of the most important forms of emotional expression. When children «adopt» stones, draw faces on fruit, or construct stories with bottle caps, they are doing what Wall-E does: bringing the inanimate to life to fill their world with meaning.

When Eve appears, Wall-E transforms. Something similar is triggered to what happens in childhood when a child experiences a secure emotional bond: they seek contact, desire to nurture, experience separation anxiety, and expose themselves emotionally. They appear vulnerable, confused, and emotional. There are no words, but there are gestures that speak volumes. The film, without discussing attachment theory, illustrates this with brutal clarity.

Meanwhile, humans float in spaceships, completely disconnected from their bodies, their environment, and each other. Children and adults alike can identify a clear critique here: the excess of stimulation, the replacement of physical movement with digital movement, the loss of authentic human bonds. Wall-E, without being human, walks, touches, feels, dances, listens. And in doing so, he reminds everyone—the characters and the viewers—of what it feels like to be alive.

Wall-E also speaks of ecology, yes. But above all, it speaks of emotional memory. Of the importance of preserving what is small. It teaches children that not everything that is old should be discarded. That what is broken can have value. That caring for the world begins with caring for what’s right in front of you: a plant, a toy, a memory, a friendship.

Cookie of the Day:

Sometimes the most heroic acts don’t make a sound. They’re more like picking up what others threw away, planting something where nothing else grows, staying when everyone else has left. If you have a quiet, thoughtful child who is fascinated by strange objects, who cares for what others ignore… maybe you have a little Wall-E at home. Teach them that this is love too. That caring for the invisible is a superpower. And that, with luck, one day that simple gesture—a plant, a glance, a shy «hello»—can save everything.

Wall-E: El robot que nos recordó cómo ser humanos

Hay películas que entretienen, otras que conmueven, y unas pocas que, sin decir casi una palabra, te enseñan lo esencial. Wall-E es una de esas. Un pequeño robot oxidado, solitario, curioso… con más humanidad que muchos humanos. En un planeta vacío, cubierto de basura, donde la civilización decidió irse porque era más fácil escapar que reparar, Wall-E sigue haciendo su trabajo. Día tras día, en silencio, recoge, acomoda, limpia. Y mientras tanto, colecciona cosas. Cosas que otros tiraron. Cosas que nadie valoró. Como quien guarda pedazos de esperanza sin saberlo.

Cuando los niños ven Wall-E, no solo están viendo a un robot adorable que se enamora de una sonda espacial moderna. Están viendo el poder de la constancia, de la ternura, de la curiosidad. Ven lo que pasa cuando alguien, en lugar de rendirse, decide cuidar. Y cuidar sin que nadie lo vea, sin que nadie lo premie, sin aplausos ni seguidores. Solo porque sí. Porque es lo correcto.

Desde la psicología infantil, Wall-E toca fibras profundas del desarrollo emocional. Wall-E vive en un entorno desolado y silencioso, y sin embargo mantiene un profundo mundo interno. Esto refleja, en muchos niños, esa capacidad para generar vínculos afectivos incluso en entornos fríos o desconectados. Wall-E representa la resiliencia emocional, esa habilidad de sostener la esperanza y la conexión aún en el aislamiento.

Además, este pequeño robot se fascina con objetos insignificantes: un tenedor, una bombilla, un cubo de Rubik. No es casual. En la infancia, el juego simbólico es una de las formas más importantes de expresión emocional. Cuando los niños “adoptan” piedras, dibujan caras en frutas, construyen historias con tapitas de botellas, están haciendo lo que hace Wall-E: darle vida a lo inanimado para llenar de sentido su mundo.

Cuando aparece Eva, Wall-E se transforma. Se activa algo similar a lo que ocurre en la infancia cuando un niño experimenta un vínculo afectivo seguro: busca el contacto, desea cuidar, siente ansiedad por separación, y se expone emocionalmente. Se muestra vulnerable, confundido, emocionado. No hay palabras, pero hay gestos que dicen todo. La película, sin hablar de teoría del apego, la ilustra con una claridad brutal.

Y mientras tanto, los humanos flotan en naves, completamente desconectados de su cuerpo, de su entorno, de los otros. Niños y adultos pueden identificar aquí una crítica clara: el exceso de estímulos, el reemplazo del movimiento físico por lo digital, la pérdida de vínculos humanos auténticos. Wall-E, sin ser humano, camina, toca, siente, baila, escucha. Y al hacerlo, les recuerda a todos —a los personajes y a los espectadores— lo que se siente estar vivo.

Wall-E también habla de ecología, sí. Pero sobre todo habla de memoria afectiva. De la importancia de preservar lo pequeño. Enseña a los niños que no todo lo que es viejo debe desecharse. Que lo roto puede tener valor. Que cuidar el mundo empieza por cuidar lo que tienes en frente: una planta, un juguete, un recuerdo, una amistad.

A veces los actos más heroicos no hacen ruido. Se parecen más a recoger lo que otros tiraron, a plantar algo donde no crece nada, a quedarse cuando todos se fueron. Si tienes un hijo silencioso, detallista, que se fascina por objetos extraños, que cuida lo que otros ignoran… tal vez tienes en casa a un pequeño Wall-E. Enséñale que eso también es amor. Que cuidar lo invisible es un súper poder. Y que, con suerte, un día ese gesto simple —una planta, una mirada, un “hola” tímido— puede salvarlo todo.

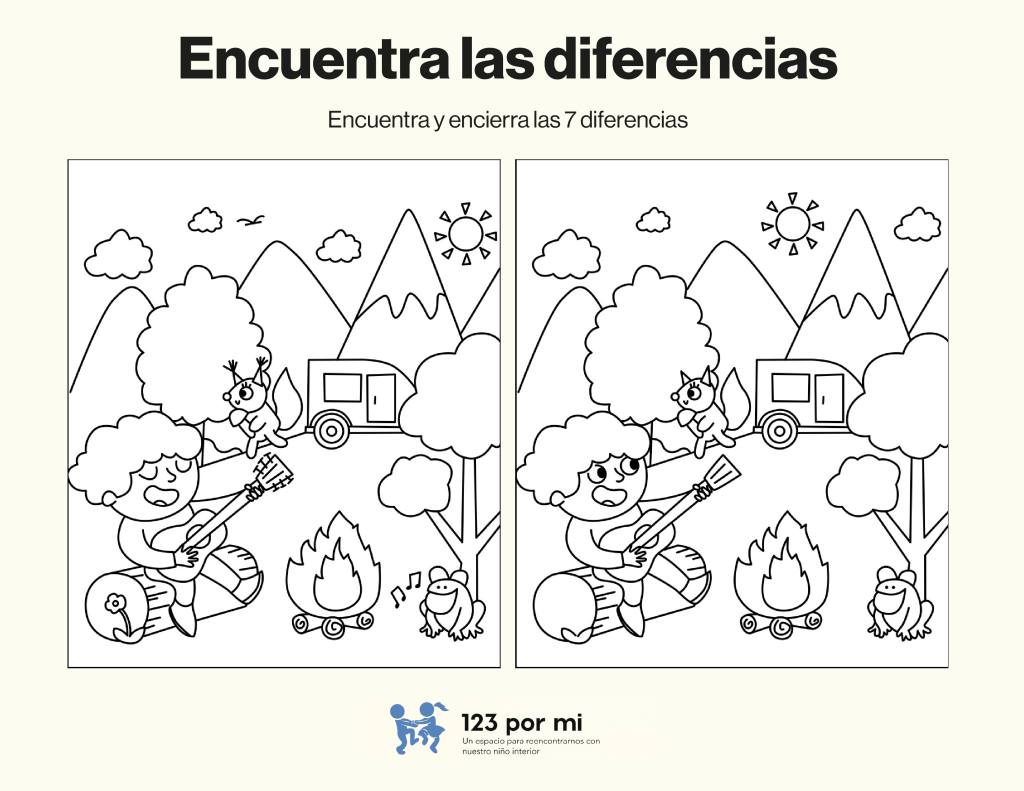

Encuentra las diferencias

Encuentra las diferencias

Encuentra las diferencias

Ratatouille: The Kitchen as a Stage for the Self

“Anyone can cook.” That’s how Ratatouille begins and ends, but it’s not really a movie about food. It’s a movie about possibility. About breaking molds. About what happens when you let your desire be stronger than your destiny. And yes: it’s also a movie about rats. But, above all, about dreams that make their way, even through the cracks of a system that tells you no.

Remy is a mouse, an outcast even within his own colony because he has a more refined palate and a different view of the world. From a developmental psychology perspective, we could understand Remy as a subject in search of individuation, that process described by Carl Jung in which the self differentiates itself from the collective to assert itself as an autonomous and creative identity.

Remy doesn’t want to eat junk. He wants to create. He wants to feel. It’s not enough to survive. He wants to live, and living involves choosing. This puts him in constant tension with his environment, which represents security, tradition, the «that’s the way things are.» Instead, Remy chooses the path of art. Because yes: cooking, here, is art. It’s sensitivity. It’s expression.

Ratatouille also represents the figure of the «ideal self» (Rogers), that internal model that guides our actions toward what we would like to be. For Remy, that ideal is Gusteau, the dead chef turned into an inner conscience. A voice that accompanies him, that reminds him that it’s possible. To dream. To never give up. That even as a rat, he can aspire to excellence.

The bond with Linguini, that clumsy human who can’t even fry an egg, functions as a metaphor for the synergy between the instinctive and the structured, between passion and form. Together they cook not because they are perfect, but because they learn to trust. From a Vygotskian perspective, we could say that Linguini is the cultural mediator that allows Remy to transition from internal thought to social language. And vice versa.

The kitchen, rigid, hierarchical, and hostile, represents the adult world: that space where creativity is often repressed by the fear of error. But Remy breaks through with flavor. His final ratatouille—that humble, peasant, unpretentious dish—is the masterstroke: because it moves, because it connects, because it says «this is me.»

And here appears one of the most beautiful moments from the perspective of emotional psychology: the scene in which Anton Ego, the feared critic, tastes the dish and is emotionally transported back to his childhood. That sudden connection with an early memory, evoked by flavor, is a clear example of the phenomenon of episodic memory and the power of the senses as an activator of affective memories. A stimulus that, as Proust would say, restores lost time. Ego, who represents cold reason, eventually surrenders to emotional authenticity.

And of course, Ratatouille also has its «cookie crisis.» Or rather: its «hat crisis.» When it’s revealed that the cook is a rat, everything collapses. The system doesn’t accept anything different. Talent, if it comes from an unexpected place, is discarded. But the film insists: value doesn’t depend on packaging. It depends on dedication, intention, passion.

And so, Ratatouille becomes a vital lesson for children and adults alike. It tells us: it doesn’t matter where you come from. What matters is what you have inside. What matters is what you do with it. Because anyone can cook. Anyone can create. But only those who dare to be true to themselves… manage to move.

Ratatouille: la cocina como escenario del yo

“Cualquiera puede cocinar”. Así comienza y termina Ratatouille, pero no es realmente una película sobre comida. Es una película sobre posibilidad. Sobre romper moldes. Sobre lo que pasa cuando dejas que tu deseo sea más fuerte que tu destino. Y sí: también es una película sobre ratas. Pero, sobre todo, sobre sueños que se abren paso, incluso entre las grietas de un sistema que te dice que no.

Remy es un ratón, un marginado incluso dentro de su propia colonia por tener un paladar más fino y una mirada distinta del mundo. Desde la psicología del desarrollo, podríamos entender a Remy como un sujeto en búsqueda de individuación, ese proceso descrito por Carl Jung en el que el yo se diferencia del colectivo para afirmarse como una identidad autónoma y creativa.

Remy no quiere comer basura. Quiere crear. Quiere sentir. No basta con sobrevivir. Él quiere vivir, y vivir implica elegir. Esto lo pone en constante tensión con su entorno, que representa la seguridad, la tradición, el “así son las cosas”. En cambio, Remy elige el camino del arte. Porque sí: cocinar, aquí, es arte. Es sensibilidad. Es expresión.

En Ratatouille se representa también la figura del “yo ideal” (Rogers), ese modelo interno que orienta nuestras acciones hacia lo que quisiéramos ser. Para Remy, ese ideal es Gusteau, el chef muerto convertido en conciencia interior. Una voz que lo acompaña, que le recuerda que es posible. Que sueñe. Que no se rinda. Que aún siendo rata, puede aspirar a la excelencia.

El vínculo con Linguini, ese humano torpe que no sabe ni freír un huevo, funciona como una metáfora de la sinergia entre lo instintivo y lo estructurado, entre la pasión y la forma. Juntos cocinan no porque sean perfectos, sino porque aprenden a confiar. Desde una perspectiva vygotskiana, podríamos decir que Linguini es el mediador cultural que permite a Remy transitar del pensamiento interno al lenguaje social. Y viceversa.

La cocina, rígida, jerárquica y hostil, representa el mundo adulto: ese espacio donde la creatividad suele ser reprimida por el miedo al error. Pero Remy se abre paso con sabor. Su ratatouille final —ese plato humilde, campesino, sin pretensiones— es el golpe maestro: porque emociona, porque conecta, porque dice “esto soy yo”.

Y aquí aparece uno de los momentos más bellos desde la psicología emocional: la escena en la que Anton Ego, el crítico temido, prueba el plato y vuelve emocionalmente a su infancia. Esa conexión súbita con una memoria temprana, evocada por el sabor, es un ejemplo claro del fenómeno de la memoria episódica y el poder sensorial como activador de recuerdos afectivos. Un estímulo que, como diría Proust, devuelve el tiempo perdido. Ego, que representa la razón fría, termina rindiéndose ante la autenticidad emocional.

Y por supuesto, cuando se revela que quien cocina es una rata, todo se derrumba. El sistema no acepta lo distinto. El talento, si viene de un lugar inesperado, se desecha. Pero la película insiste: el valor no depende del envoltorio. Depende de la entrega, la intención, la pasión.

Y así, Ratatouille se convierte en una lección vital para chicos y grandes. Nos dice: no importa de dónde vengas. Importa lo que llevas dentro. Importa lo que haces con eso. Porque cualquiera puede cocinar. Cualquiera puede crear. Pero solo los que se atreven a ser fieles a sí mismos… logran emocionar.